Visibility and sight distance are parameters central to the inherent safety of intersections, driveways, and other potential conflict points. Intersection design should facilitate eye contact between street users, ensuring that motorists, bicyclists, pedestrians, and transit vehicles intuitively read intersections as shared spaces. Visibility can be achieved through a variety of design strategies, including intersection “daylighting,” design for low-speed intersection approaches, and the addition of traffic controls that remove trees or amenities that impede standard approach, departure, and height sight distances. Sight line standards for intersections should be determined using target speeds, rather than 85th-percentile design speeds. This prevents wide setbacks and designs that increase speeds and endanger pedestrians.

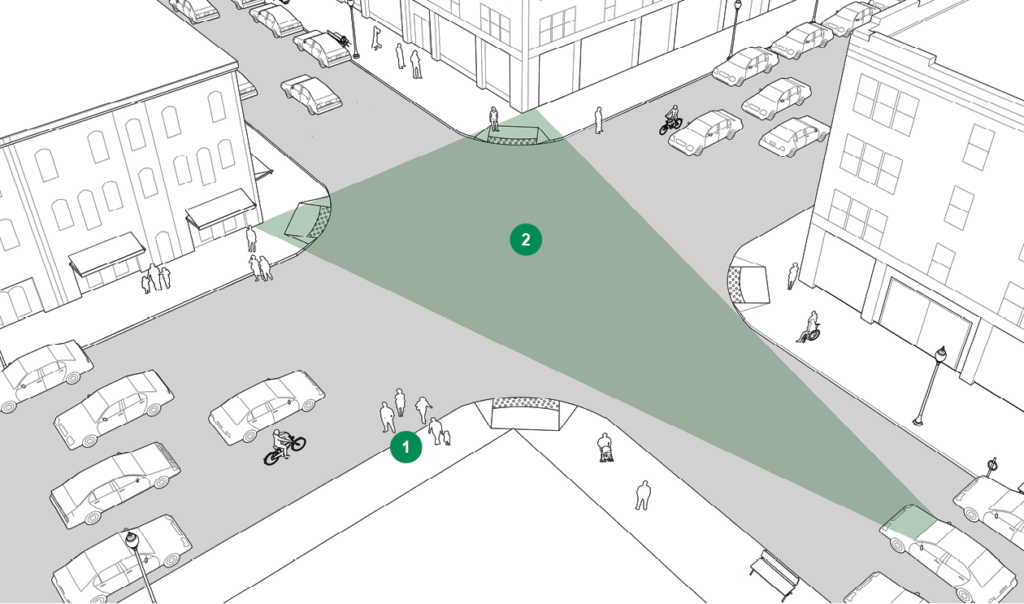

Lower speeds at urban intersections with insufficient sight distances. Low speeds yield smaller sight triangles, meaning that drivers can focus on less activity and better react to potential conflicts.

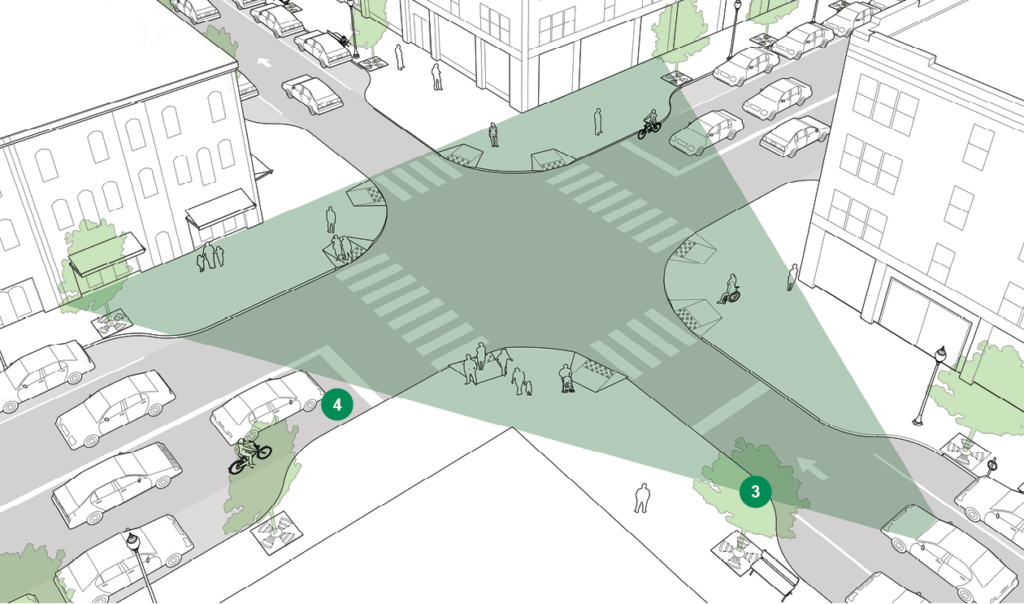

Intersections with insufficient visibility should be reconstructed to be more compact. Compact intersections place more activity within the sight triangle, giving all users a better view of potential conflicts.

Discussion

Visibility is impacted by the design and operating speed of a roadway. Determining sightlines based on existing or 85thpercentile speeds is not sufficient in all cases. Designers need to proactively lower speeds near conflict points to ensure that sightlines are adequate and movements predictable, rather than widening the intersection or removing sightline obstacles.

Sight triangles required for stopping and approach distances are typically based upon ensuring safety at intersections with no controls at any approach. This situation rarely occurs in urban environments, and occurs only at very low-speed, low-volume junctions. At uncontrolled locations where volume or speed present safety concerns, add traffic controls or traffic calming devices on the intersection approach.1

1In urban areas, corners frequently act as a gathering place for people and businesses, as well as the locations of bus stops, bicycle parking, and other elements. Design should facilitate eye contact between these users, rather than focus on the creation of clear sightlines for moving traffic only.

2Wide corners with large sight triangles may create visibility, but in turn may cause cars to speed through the intersection, losing the peripheral vision they might have retained at a slower and more cautious speed.

In certain circumstances, an object in the roadway or on the sidewalk may be deemed to obstruct sightlines for vehicles in a given intersection and to pose a critical safety hazard. Removal of the object in question is a worst case scenario based on significant crash risk and crash history. Many objects, such as buildings, terrain features, trees in historic districts, and other more permanent parts of the landscape should be highlighted using warning signage and other features, rather than removed.

While this uncontrolled intersection operates at low speeds, it may still benefit from stop

control or traffic calming.

Critical

In determining the sight distance triangle for a given intersection, use the target speed, rather than the design speed, for that intersection.

3Fixed objects, such as trees, buildings, signs, and street furniture, deemed to inhibit the visibility of a given intersection and create safety concerns, should not be removed without the prior consideration of alternative safety mitigation measures, including a reduction in traffic speeds, an increase in visibility through curb extensions or geometric design, or the addition of supplementary warning signs.

Traffic control devices must be unobstructed in the intersection, and shall be free of tree cover or visual clutter.

Recommended

4Daylight intersections by removing parking within 20–25 feet of the intersection.2

Site street trees at a 5-foot minimum from the intersection, aligning the street tree on the near side of the intersection with the adjacent building corner. Street trees should be sited 3 feet from the curb return and 5 feet from the nearest stop sign.3

Lighting is crucial to the visibility of pedestrians, bicyclists, and approaching vehicles. Major intersections and pedestrian safety islands should be adequately lit with pedestrian-scaled lights to ensure visibility. In-pavement flashing lights can enhance crossing visibility at night, but should be reinforced by well-maintained retro reflective markings.4

Street trees enhance the public realm and are often sited close to intersections without inducing safety concerns.

Pedestrian-scale lighting illuminates the sidewalk and adjacent storefronts.

Optional

Additional signage may be provided to enhance visibility at a given intersection, but should not replace geometric design strategies that increase visibility.

Signage, in combination with a raised crosswalk, improves visibility at this right-turn lane.

- Vehicle codes state that drivers must yield to drivers on the right, which necessitates slowing down.

City of Portland, Oregon, “Uncontrolled Intersections and You,” accessed June 3, 2013, http://www.portlandoregon.gov/transportation/article/284482. ↩︎ - Parking is typically restricted within 10–25 feet of a crosswalk. San Francisco uses 10 feet; New Jersey adopted 25 feet within a marked or unmarked crosswalk.

New Jersey, New Jersey statutes annotated: Title 39 :4 Motor vehicles and traffic regulation.

FHWA Safety Program, “Remove/Restrict Parking,” accessed June 3, 2013, http://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/saferjourney/library/countermeasures/56.htm. ↩︎ - San Francisco standards allow trees 25 feet from the near-side and 5 feet from the far-side curbs.

“Guidelines for Planting Street Trees,” San Francisco Department of Public Works, accessed June 3, 2013, http://www.sfdpw.org/Modules/ShowDocument.aspx?documentid=622.

Elizabeth Macdonald, Alethea Harper, Jeff Williams, and Jason A. Hayter, Street trees and Intersection Safety, (Berkley: Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California at Berkeley, 2006). ↩︎ - Pedestrian scale lighting may be added to existing vehicle poles or between poles.

Complete Streets Complete Networks—A Manual for the Design of Active Transportation (Chicago: Active Transportation Policy, 2012).

Spacing depends upon existing lighting available, roadway width, and quality of lighting, but in general lighting every 50 feet provides a secure nighttime walking atmosphere.

Project for Public Spaces, “Lighting Use & Design,” accessed June 3, 2013, http://www.pps.org/reference/streetlights/. ↩︎