The width allocated to lanes for motorists, buses, trucks, bikes, and parked cars is a sensitive and crucial aspect of street design. Lane widths should be considered within the assemblage of a given street delineating space to serve all needs, including travel lanes, safety islands, bike lanes, and sidewalks.

Each lane width discussion should be informed by an understanding of the goals for traffic calming as well as making adequate space for larger vehicles, such as trucks and buses.

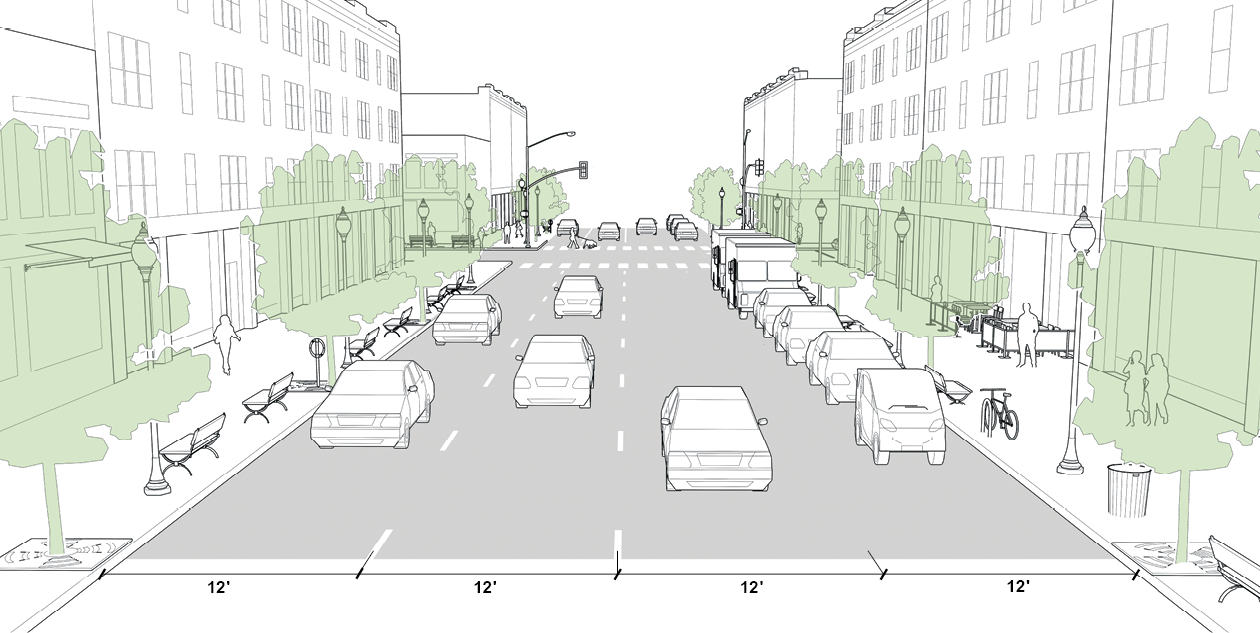

Travel lanes are striped to define the intended path of travel for vehicles along a corridor. Historically, wider travel lanes (11–13 feet) have been favored to create a more forgiving buffer to drivers, especially in high-speed environments where narrow lanes may feel uncomfortable or increase potential for side-swipe collisions.

Lane widths less than 12 feet have also historically been assumed to decrease traffic flow and capacity, a claim new research refutes.1

Discussion

The relationship between lane widths and vehicle speed is complicated by many factors, including time of day, the amount of traffic present, and even the age of the driver. Narrower streets help promote slower driving speeds. which in turn reduce the severity of crashes. Narrower streets have other benefits as well, including reduced crossing distances, shorter signal cycles, less stormwater, and less construction material to build.

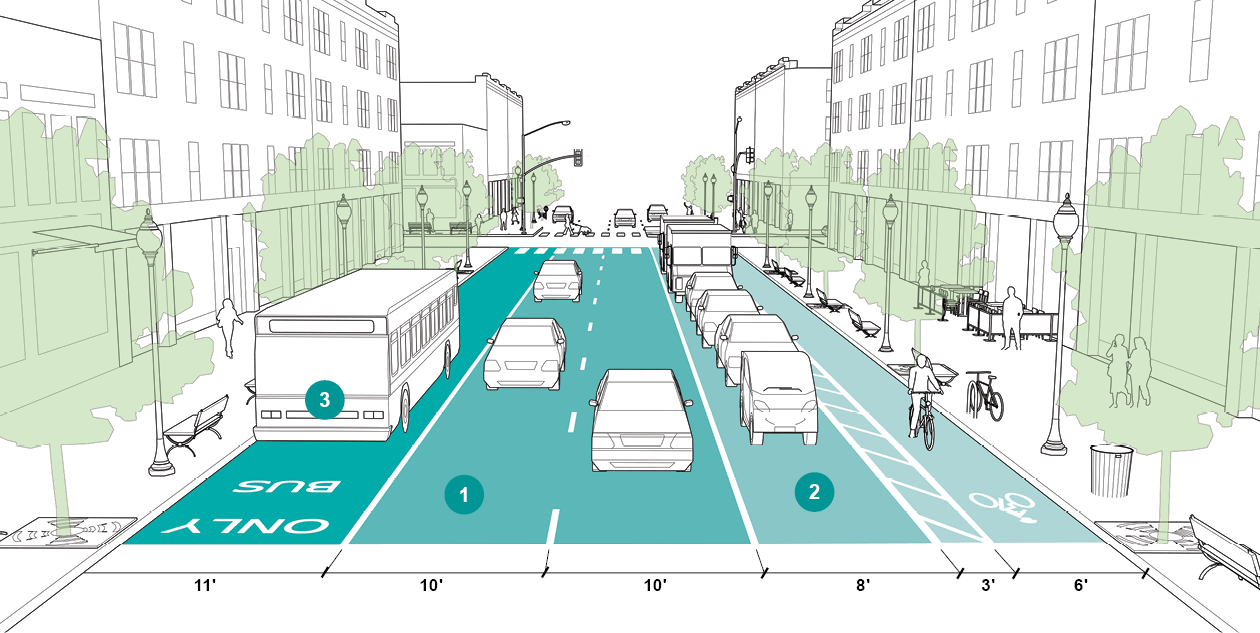

Lane widths of 10 feet are appropriate in urban areas and have a positive impact on a street’s safety without impacting traffic operations. For designated truck or transit routes, one travel lane of 11 feet may be used in each direction. In select cases, narrower travel lanes (9–9.5 feet) can be effective as through lanes in conjunction with a turn lane.2

Recommended

Lanes greater than 11 feet should not be used as they may cause unintended speeding and assume valuable right-of -way at the expense of other modes.

Restrictive policies that favor the use of wider travel lanes have no place in constrained urban settings, where every foot counts. Research has shown that narrower lane widths can effectively manage speeds without decreasing safety and that wider lanes do not correlate to safer streets.3 Moreover, wider travel lanes also increase exposure and crossing distance for pedestrians at inter-sections and midblock crossings.4

Use striping to channelize traffic, demarcate the road for other uses, and minimize lane width.

Striping should be used to delineate parking and curbside uses from the travel lane.

1Lane width should be considered within the overall assemblage of the street. Travel lane widths of 10 feet generally provide adequate safety in urban settings while discouraging speeding. Cities may choose to use 11-foot lanes on designated truck and bus routes (one 11-foot lane per direction) or adjacent to lanes in the opposing direction.

Additional lane width may also be necessary for receiving lanes at turning locations with tight curves, as vehicles take up more horizontal space at a curve than a straightaway.

Wide lanes and offsets to medians are not required but may be beneficial and necessary from a safety point of view.

Optional

2 Parking lane widths of 7–9 feet are generally recommended. Cities are encouraged to demarcate the parking lane to indicate to drivers how close they are to parked cars. In certain cases, especially where loading and double parking are present, wide parking lanes (up to 15 feet) may be used. Wide parking lanes can serve multiple functions, including as indus-trial loading zones or as an interim space for bicyclists.

3 For multilane roadways where transit or freight vehicles are present and require a wider travel lane, the wider lane should be the outside lane (curbside or next to parking). Inside lanes should continue to be designed at the minimum possible width. Major truck or transit routes through urban areas may require the use of wider lane widths.

2-way streets with low or medium volumes of traffic may benefit from the use of a dashed center line with narrow lane widths or no center line at all. In such instances, a city may be able to allocate additional right-of-way to bicyclists or pedestrians, while permitting motorists to cross the center of the roadway when passing.

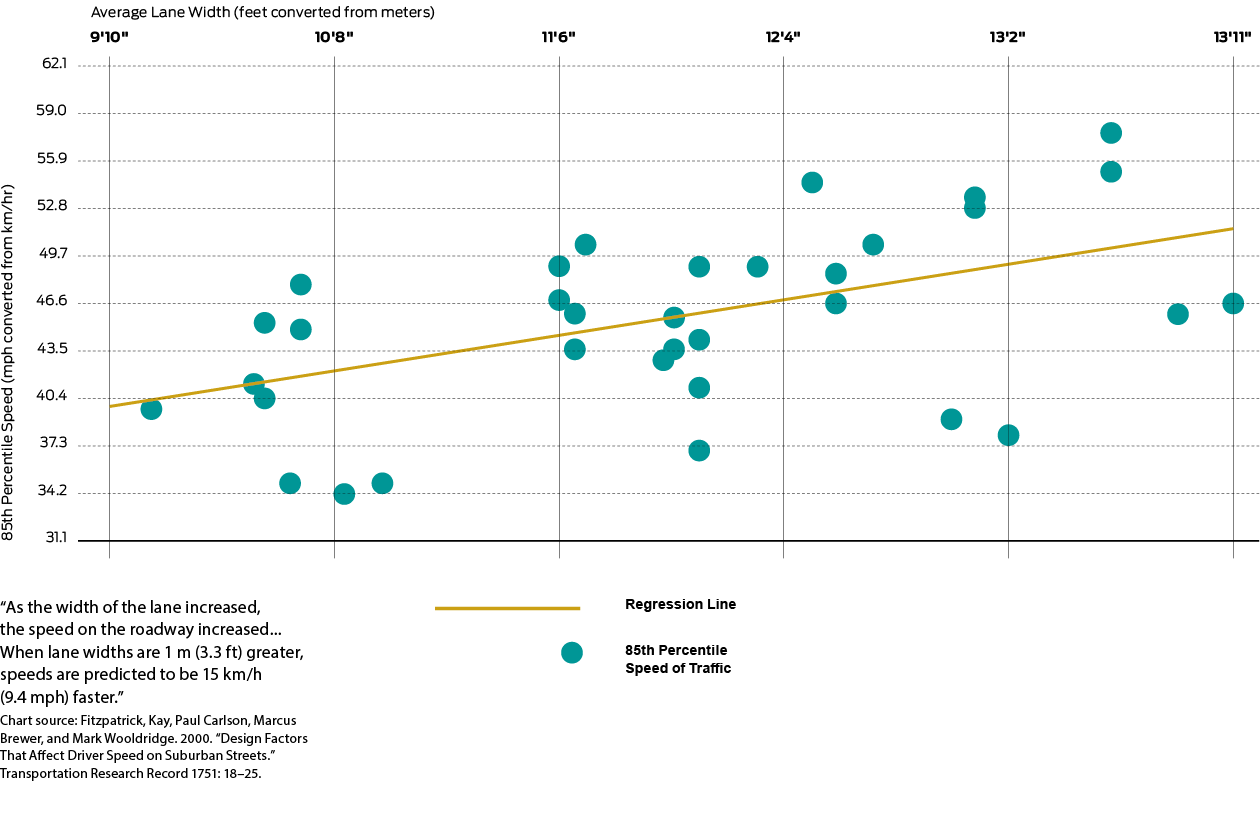

Wider travel lanes are correlated with higher vehicle speeds.

- Theo Petrisch, “The Truth about Lane Widths,” The Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center, accessed April 12, 2013, http://www.bicyclinginfo.org/library/details.cfm?id=4348. ↩︎

- Research suggests that lane widths less than 12 feet on urban and suburban arterials do not increase crash frequencies.

Ingrid Potts, Douglas W. Harwood, and Karen R. Richard, “Relationship of Lane Width to Safety on Urban and Suburban Arterials,” (paper presented at the TRB 86th Annual Meeting, Washington, D.C., January 21–25, 2007).

Relationship Between Lane Width and Speed, (Washington, D.C.: Parsons Transportation Group, 2003), 1–6.

↩︎ - Eric Dumbaugh and Wenhao Li, “Designing for the Safety of Pedestrians, Cyclists, and Motorists in Urban Environments.” Journal of the American Planning Association 77 (2011): 70.

Previous research has shown various estimates of the relationship between lane width and travel speed. One account estimated that each additional foot of lane width related to a 2.9 mph increase in driver speed.

Kay Fitzpatrick, Paul Carlson, Marcus Brewer, and Mark Wooldridge, “Design Factors That Affect Driver Speed on Suburban Arterials”: Transportation Research Record 1751 (2000): 18–25.

Other references include:

Potts, Ingrid B., John F. Ringert, Douglas W. Harwood and Karin M. Bauer. Operational and Safety Effects of Right-Turn Deceleration Lanes on Urban and Suburban Arterials. Transportation Research Record: No 2023, 2007.

Macdonald, Elizabeth, Rebecca Sanders and Paul Supawanich. The Effects of Transportation Corridors’ Roadside Design Features on User Behavior and Safety, and Their Contributions to Health, Environmental Quality, and Community Economic Vitality: a Literature Review. UCTC Research Paper No. 878. 2008. ↩︎ - Longer crossing distances not only pose as a pedestrian barrier but also require longer traffic signal cycle times, which may have an impact on general traffic circulation. ↩︎