“Conference Cliff Notes” is a series of short blog posts summarizing big takeaways and interesting ideas from NACTO’s 2023 Designing Cities Conference in Denver. You can read more about the conference here.

From left to right: Moderator Kris Chandler (NACTO), Kimberly Vacca (DDOT), Jaclyn Garcia (LADOT) and Emily Weidenhof (NYCDOT).

In the early days of COVID-19 pandemic, outdoor dining and open street initiatives became a public health lifeline that allowed people to connect and businesses to operate in safe and accessible ways. More than three years later, these programs have become a celebrated part of many urban streetscapes. But cities are also facing difficult questions about what the future of these programs will hold, and how they can use their limited resources, public space and political capital to integrate them with other public right-of-way initiatives.

These questions were at the center of “Making Space for Making Place: The Future of Open Streets and Outdoor Dining,” a breakout session at the #NACTO2023 Designing Cities Conference, where three leaders in public space activation explained how their cities are managing–and reimagining–their open streets and outdoor dining programs to enable community connections.

“We’re grappling with this question of, what do we do with our downtowns now that people are gone?” explained Kimberly Vacca, Public Space Activation Coordinator at the District Department of Transportation (DDOT) in Washington, D.C. “What brings people to these spaces? We need to create space for them to come. These programs do that.”

DDOT’s public space activation work comes in the form of several different programs, including Sidewalk Cafes, Parking Lane Streateries, Travel Lane Streateries, an Open Streets Program, an Arts in the Right-of-Way Program, and a Block Parties Program. These programs share the same overarching goal: they are designed and managed to be people-focused, promoting livability and public health by improving accessibility, sustainability, safety, and placemaking. But having a variety of initiatives has also allowed the agency to diversify its approach, and to view the streetscape as a canvas it can design in different ways.

DDOT’s public space activation programming.

See more slides from this presentation. >

“Neighborhoods in our city that have done these programs have stayed vibrant,” said Vacca. “Businesses say that’s what saved them. This is what sold it to our council and our mayor.”

A variety of tools also means a complicated variety of rules and regulations, and DDOT is still in the process of shifting its efforts from pandemic-era ad-hoc initiatives to more permanent programs. To grapple with that challenge, DDOT has worked in tandem with other frontline city agencies, then engaged stakeholders and partners like restaurant associations, BIDs, and neighborhood advisory commissions in ways that are most meaningful and relevant to those partners.

“All that has helped us develop permanent regulations,” Vacca explained. “But we’re also creating a working, breathing guideline document, with illustrations restaurant owners can understand.”

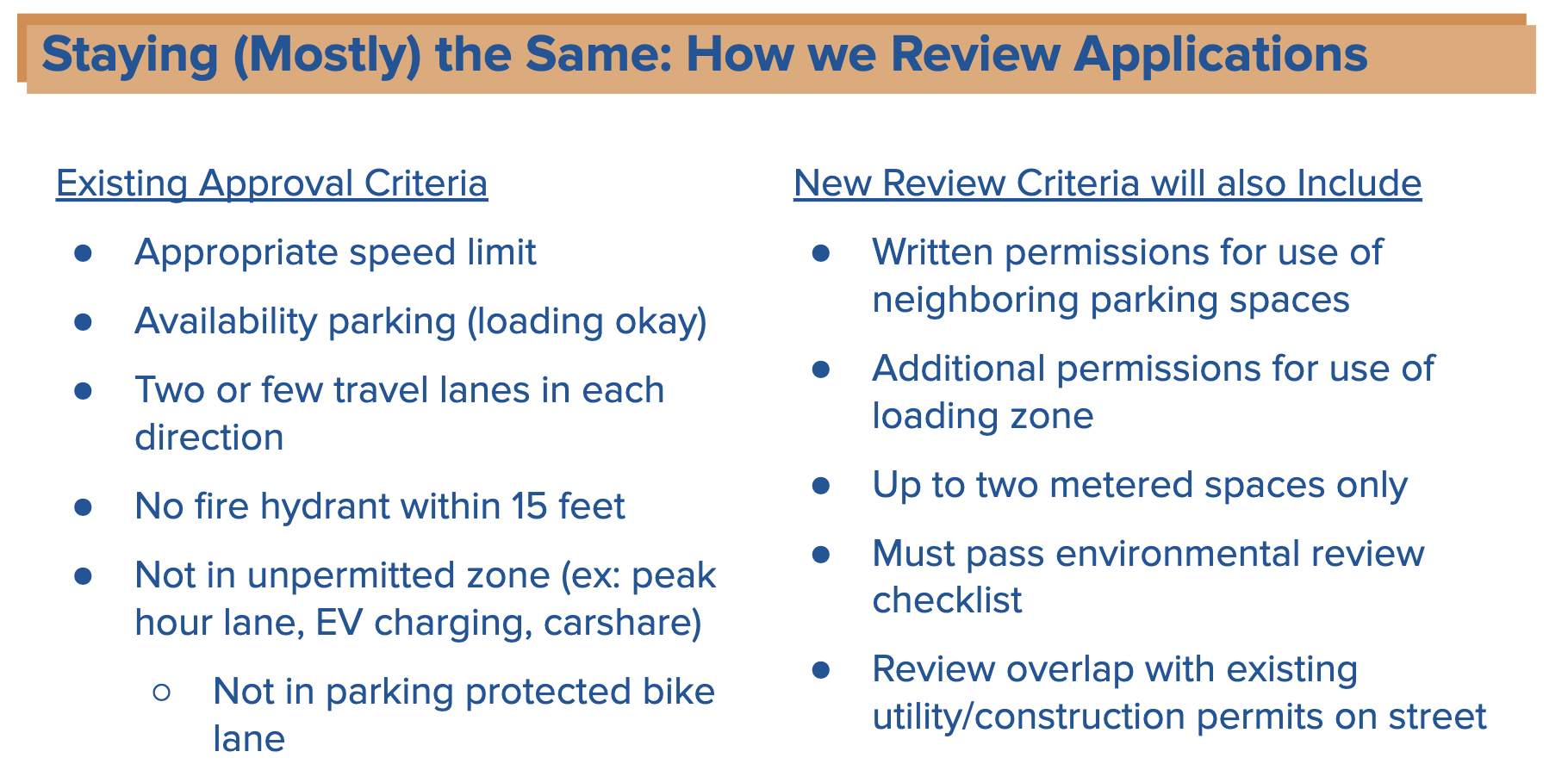

The Los Angeles Department of Transportation (LADOT) has taken a similar approach to its LA Al Fresco program, through which the City has sought to standardize its approval process for outdoor dining by detailing a new set of criteria for dining facilities and practices. Like their counterparts in D.C., LADOT first worked with other city agencies to set internal standards before engaging restaurant owners.

“We know restaurant owners tend to be busy people, and they may not have time to look at a document online,” said Jaclyn Garcia, a Supervising Transportation Planner at LADOT. “So we’re trying to provide a lot of different avenues of communication. We will have a hotline so they can call.”

LADOT’s changing approach to approving and regulating outdoor dining structures.

Through the pandemic, the City identified consistent challenges, ranging from a lack of dedicated staffing and dedicated design standards to inconsistent enforcement policies for unpermitted structures. As the agency has iterated on the program, they’ve worked to create approval criteria, set design standards for facilities and structures, and implement operational rules that businesses must comply with.

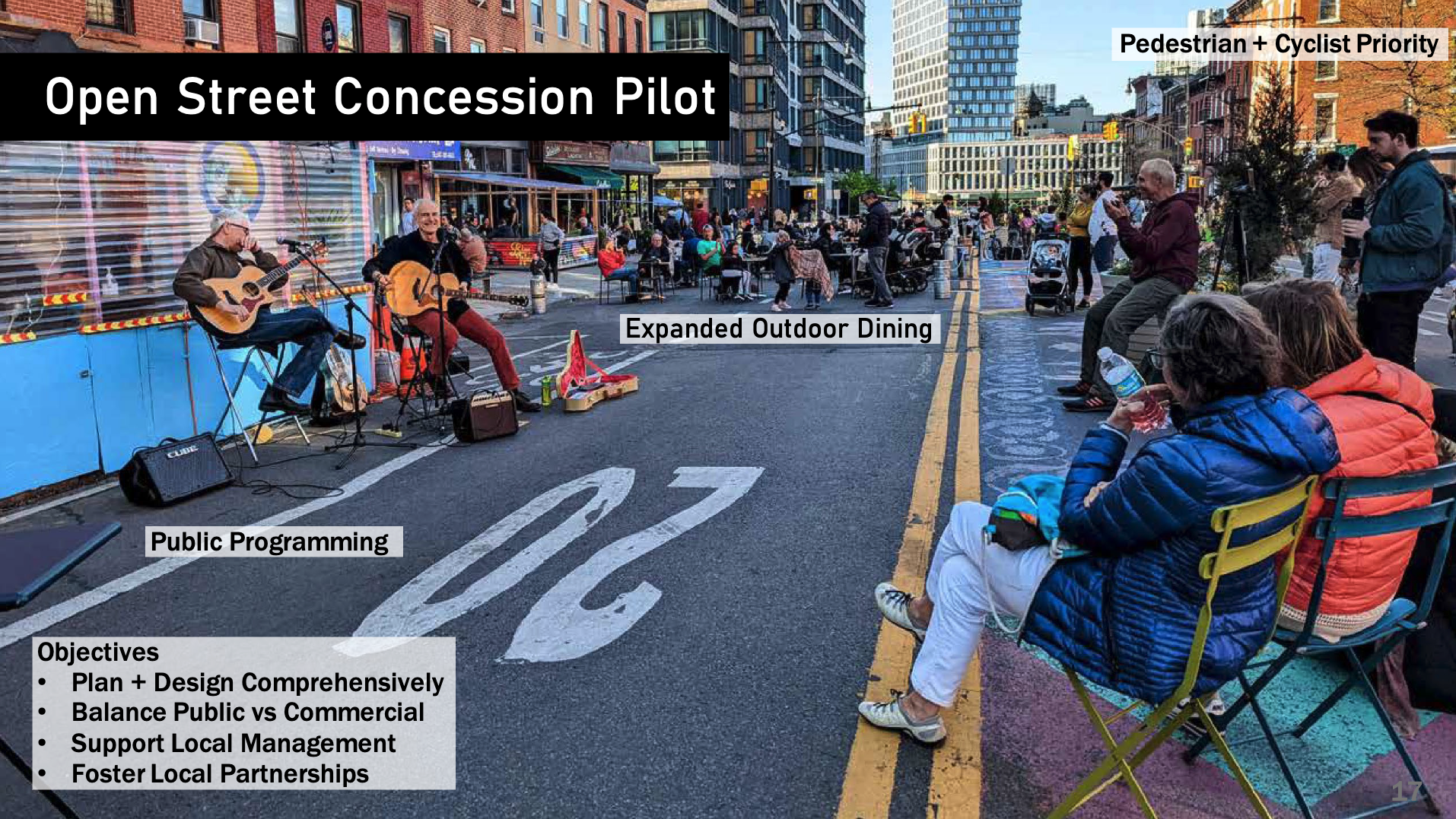

Successfully implementing permanent outdoor dining and open streets programs often means finding the right balance between consistency and flexibility. In developing its own programs, the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) intentionally sought to look “beyond the binary” to create design tool-kits that are flexible and responsive to a variety of circumstances, and allow the city to integrate open streets programming with other pedestrian, cycling and transit priorities.

“How do we use the demand for open streets and restaurants to create a more comprehensive management framework?” asked Emily Weidenhof, NYCDOT’s Director of Public Space. “We’re really thinking beyond the binary of streets just being open or closed.”

NYCDOT’s toolkit for designing and programming public spaces “beyond the binary.”

That mindset can allow cities to advance equity goals by establishing public space programming in a wide variety of neighborhoods, even those far from the traditional central business districts. In refashioning streets into public spaces, cities can also make them into vehicles for local advocacy, and offer community members and local businesses greater opportunity to shape the way their streets are used.

“We’re always thinking about how we’re going to keep these spaces relevant and thriving,” Weidenhof said. “Through concession and programming opportunities, we can bring neighborhood civic and cultural life to a wider audience.”