The federal government is in the final stages of updating outdated regulations that contribute to the traffic safety crisis. Here are the key changes we’ll be looking out for.

For decades, a little-known federal document has played an outsized role in the unsafe design of streets across the United States. This document, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (a.k.a., the MUTCD) is riddled with fundamental problems, and hasn’t been substantially updated in over half a century.

Now, the Federal Highway Administration has finished drafting a new, 11th edition of the MUTCD. The document is being reviewed by the federal Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Once the OMB approves the new Manual–likely later this summer or fall–it will be published and go into legal effect, shaping the design of U.S. streets for years to come.

Why does this matter? The U.S. is in the midst of a traffic safety crisis. More than 40,000 people per year die on American roads, a far higher number than that of any other industrialized country. Pedestrian deaths, in particular, are at a forty-year high. The costs of this crisis are not borne equally; Black people are struck and killed by drivers at an 82% higher rate than White, non-Hispanic/Latine Americans.

While all levels of government are responsible, the crisis stems in no small part from the federal standards used to build our streets. The MUTCD governs all road markings, stop signs, and traffic lights in the U.S., and prioritizes moving vehicles quickly at the expense of safety, sustainability, and accessibility for people walking, biking, using a wheelchair, or riding transit.

Under today’s MUTCD, someone crossing a street is less important than the fast-flowing movement of cars. Often, even multiple people dying at an intersection is not enough for the MUTCD to recommend installing a walk signal. Because of these flawed rules, American streets are unsafe and unwelcoming, limiting possibilities to create the vibrant, walkable neighborhoods that people want.

Smart, thoughtful changes to the MUTCD can reshape our streets and save lives. Here are six key reforms we’ll be looking for as the MUTCD is released:

- Elevate the goal of eliminating serious injuries and deaths as a guiding principle of the Manual, ensuring a “safe systems” approach throughout. The Manual unrealistically identifies target road users as pedestrians and bicyclists who always act “alertly and attentively”, “reasonably and prudently”, and “in a lawful manner.” This definition fails to recognize the inevitability of human error as well as the enormous range of urban street users. Most children, for example, would not meet this standard. Currently, the Manual implies engineers are only responsible for protecting road users who meet this impractical definition. Eliminating this language and redefining the Manual’s primary goal to prioritize safety above uniformity are essential to ensure the MUTCD serves to improve safety and accessibility for people, rather than simply reducing delays for motor vehicles.

- Remove guidance recommending the use of free-flow speeds, including the 85th percentile speed, in setting speed limits. Research shows that using the 85th percentile approach to establish speed limits leads to increases in speed–and decreases in safety–over time. That’s why organizations ranging from the National Committee on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, the National Safety Council, NACTO, and the Vision Zero Network no longer endorse the MUTCD’s recommended speed-limit-setting approach. The FHWA has downgraded the 85th percentile approach from a requirement to a recommendation, but this still sends the message that engineers can continue using this highway-based tool on urban streets. Eliminating this guidance aligns with FHWA’s intent to heed the most relevant safety research, and signals to state DOTs that this approach is no longer nationally endorsed.

- Make it safer to cross the street by reforming signal and hybrid beacon warrants so practitioners can install protected street crossings without requiring pedestrians to risk their lives. To justify installing pedestrian signals, the MUTCD requires a very high volume of people to already be crossing the unprotected–or waiting for multiple traffic injuries or deaths to occur. Motor vehicle signals, meanwhile, are routinely installed simply on the basis of traffic projections from a new development. Pedestrian warrant volumes are much higher than in other industrialized countries with far lower traffic fatalities, including Canada. In some cases, the Manual’s unreasonably restrictive warrants prevent practitioners from installing safe crossings, even when they expect that a fatality or serious injury may occur. FHWA can begin to address the double-standard by adding a simple “non-motorized network: warrant, adopting basic guidelines about how far pedestrians can be expected to walk to get to a crosswalk, and by following its own research about what kinds of streets aren’t safe enough to cross without a signal.

- Remove the Manual’s new proposed chapter on Autonomous Vehicles. The Manual’s new chapter on Autonomous Vehicles absolves AV companies of the responsibility to build vehicles that keep road users safe within the existing transportation network. Proposed requirements for street markings could cost taxpayers billions of dollars; if the markings are non-compliant and an AV-involved crash occurs, taxpayers will likely foot the bill for that, too. FHWA should remove this new AV chapter and consult with transportation practitioners, including those who build and maintain urban roadways, on appropriate AV requirements. AV development simply is not advanced enough to warrant a separate section at this time.

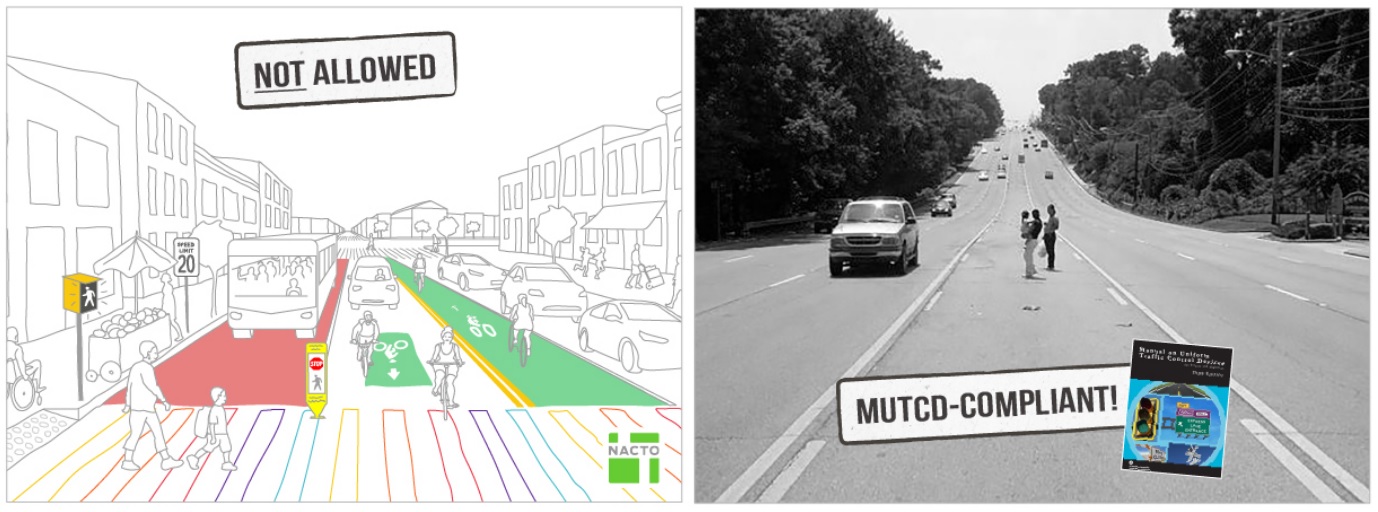

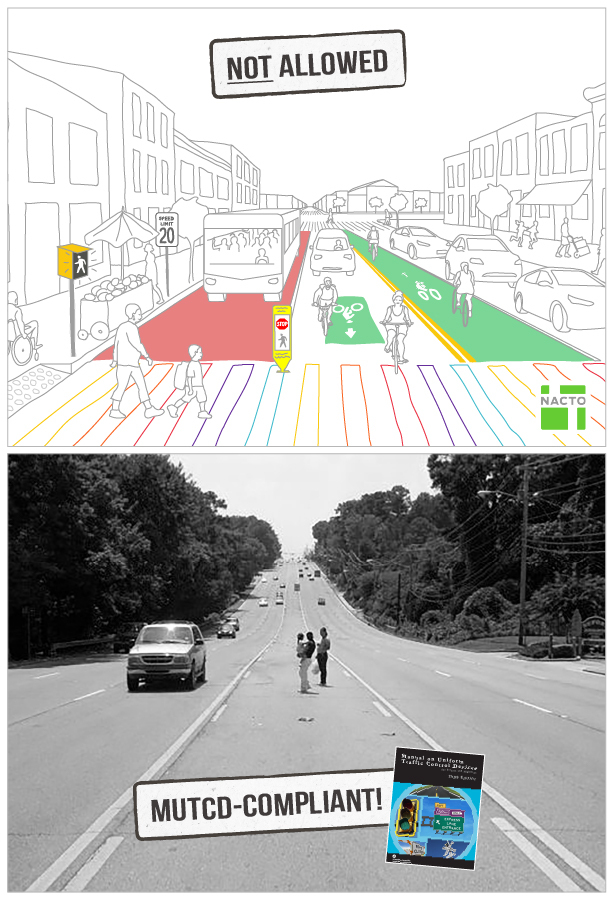

- Remove unnecessary restrictions on the use of green paint for bike lanes, red paint for bus lanes, and other colored paint for crosswalks. For no obvious reason, the proposed update to the MUTCD prevents practitioners from using green paint to delineate select bike facilities, red paint for some transit lanes, and other colored paints to create artful crosswalks. This use of colored pavement in bus and bike lanes is an important and frequently-utilized approach to delineate street space, and improves visibility for cyclists and transit vehicles. In crosswalks, colorful paint can contribute to creating a sense of place and community, and there is no evidence to prove that these designs reduce safety.

- Eliminate geometric design restrictions for urban bikeways. The MUTCD is not intended to be geometric design guidance, but it includes dozens of recommendations about geometric design details. Many are remnants of an outdated preference for vehicular-style cycling, and have been contradicted by decades of safety and operational studies. These include restrictions on placing bike lanes to the right of a right-turn lane, and unwarranted recommendations against using bike boxes. Rather than include duplicative, conflicting guidance, the MUTCD should encourage the designs called for by best practice guidance such as MassDOT’s Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide and NACTO’s Urban Bikeway Design Guide, which have been developed with input from practitioners with expertise in urban bikeway design.

Every day, people in cities and suburbs across the U.S. suffer the consequences, sometimes fatally, of this outdated document. By making the above changes, Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg and the Biden-Harris Administration can take a big leap toward their stated vision of zero roadway fatalities, and a safer future for everyone who calls the U.S. their home.