A single federal document dictates what nearly every American street looks like–and federal regulators recently updated it for the first time since 2009.

The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) governs all road markings, speed limits, stop signs, and traffic signals nationwide. With infrequent updates and nominal changes over the decades, the document has played an outsized role in the unsafe design of our streets.

In December 2023, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) published the 11th Edition of the MUTCD, the first update to the manual in almost 15 years. In the years prior to the release, NACTO organized a campaign across our member cities, transit agencies, and dozens of partner organizations to call on FHWA to update the MUTCD into a proactive, multimodal safety regulation.

Together, we combed through the 10th Edition of the MUTCD’s 1,100+ pages and developed over 400 specific edits to substantially reframe it as a safety and sustainability-first document. The new edition reflects some of those edits, making important steps toward a safer, more people-focused transportation system.

Highlights of some of the positive changes include:

- Modernizing the method for setting speed zones: Adds a context-sensitive approach to setting speed limits that accounts for streets’ adjacent land use, pedestrian and bicyclist needs, and crash history. The 11th Edition also encourages using traffic calming and adjusting street design to prevent speeding.

- Making it easier to install crosswalks: Makes installing and improving crosswalk markings easier and aligns them with guidance and best practices. If the street is too fast, busy, or wide for a marked crosswalk alone, the MUTCD supports slowing or narrowing the street, or raising the crosswalk.

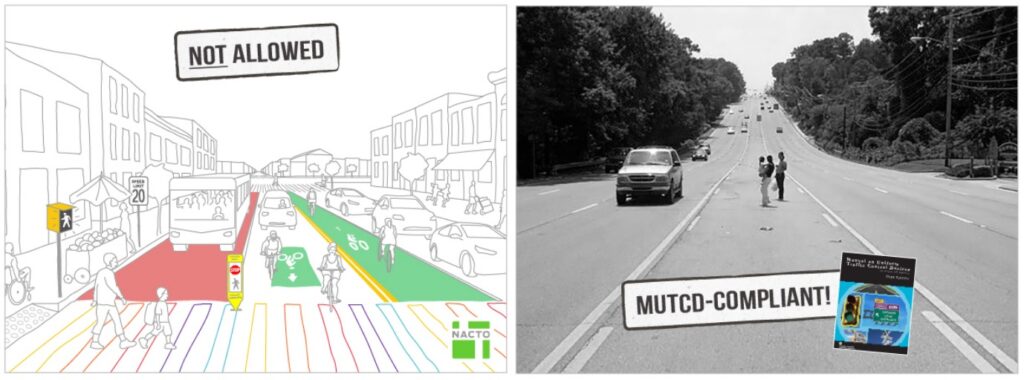

- Explicitly allowing the use of green bike lanes, red transit lanes, and asphalt art: The MUTCD now gives broad leeway to use green-painted bike lanes and red transit lanes, removing many unnecessary restrictions in previous guide versions. Asphalt art is also now explicitly allowed under the MUTCD, a significant change from the previous edition. Art is not a traffic control device and can be used both in the roadway (such as in an intersection) and outside (like in a paint-and-post curb extension or on the sidewalk). For more information, visit asphaltart.bloomberg.org/faq.

However, the 11th Edition does not include every necessary reform to create comprehensively safe streets. The MUTCD still falls short in areas that play an outsized role in the unsafe design of our streets:

- The structure of the document continues to prioritize motor vehicle movement over the enormous range of other urban street users.

- It fails to recognize the inevitability of human error: It continues to unrealistically identify target road users as pedestrians and bicyclists who always act “alertly and attentively,” “reasonably and prudently,” and “in a lawful manner.” This definition fails to recognize the inevitability of human error and the enormous range of urban street users, including children, who still deserve to be safe on our streets.

- It should go further to address pedestrian safety: To justify installing pedestrian signals, the MUTCD still requires a very high volume of people to be crossing an unprotected intersection – or that transportation officials wait for multiple traffic injuries or deaths to occur. Motor vehicle signals, meanwhile, are routinely installed simply based on traffic projections from a new development.

- It should eliminate geometric restrictions for urban bikeways and refer to best practices already successfully used in cities. The MUTCD is not intended to be geometric design guidance, but it includes dozens of recommendations about geometric design details for bicycling, which overrides local context and local engineering judgment.

- It adds language for autonomous vehicles without understanding their real-world impacts on cities. Cities should not have to adjust street design for autonomous vehicles–instead, cars should be designed to operate safely on already-existing streets. The new autonomous vehicles section has been improved, but it still should not exist.

Where do we go from here?

We must continue working to promote the changes that bring federal policy more in line with USDOT Safe System goals than previous editions.

The FHWA is already thinking about the next MUTCD update–and so are we. Here’s how we think the next iteration of this influential manual could be reframed to support safe systems:

- Developing contextual standards for urban, suburban, and rural streets that function as main streets through developed areas. These areas are distinct from freeways, expressways, or rural highways outside of urbanized locations and require different standards.

- Experimentation and innovation should be used to expand the state of the practice, revisit long-held assumptions, and update practices to meet modern needs.

- Establishing a more open process for gathering input from transportation practitioners in developed areas: By law, FHWA must now update the MUTCD every four years. In the past, FHWA has not shared ideas or draft material with the public until the start of the formal rulemaking process. During this process, federal law prevents the agency from openly communicating with cities, advocates, and other stakeholders, making transparency and dialogue impossible. Guidance (not the standards that set the size and color of signs) needs to be developed in a format other than rulemaking–one with iterations and conversations with practitioners.

Each state has two years to adopt the updated MUTCD. NACTO is coordinating with member cities and partners to track the work in states nationwide to identify opportunities for state level changes. Stay tuned for more on this effort!

The importance of reform

Our streets are unsafe because of how they are designed. More than 40,000 people die on American roads each year, far more than in other industrialized countries. Pedestrian deaths are at a 40-year high, and the costs are not borne equally: Black people are struck and killed by drivers at a significantly higher rate than white Americans.

Every day, people across the U.S. suffer the consequences of an MUTCD that hasn’t prioritized safety for all. To save lives, we need to remove institutional roadblocks that limit cities’ ability to quickly implement better urban street design. Our national standards should support or normalize pedestrian safety treatments, all-ages-and-abilities bikeways, transit priority treatments, and complete street designs. At the center of this is our continued advocacy for reform of the MUTCD.

Learn More: Visit our webpage for the latest information about the MUTCD.